The AspireAssist Device Drains Food from Your Stomach

The FDA has approved another weight loss surgery option for the obese; is it necessary or worth it?

Forty percent of American women, and 35 percent of men, are obese. Many have struggled for years with diets, and the most severely obese are hearing recommendations for weight-loss surgery from their doctors.

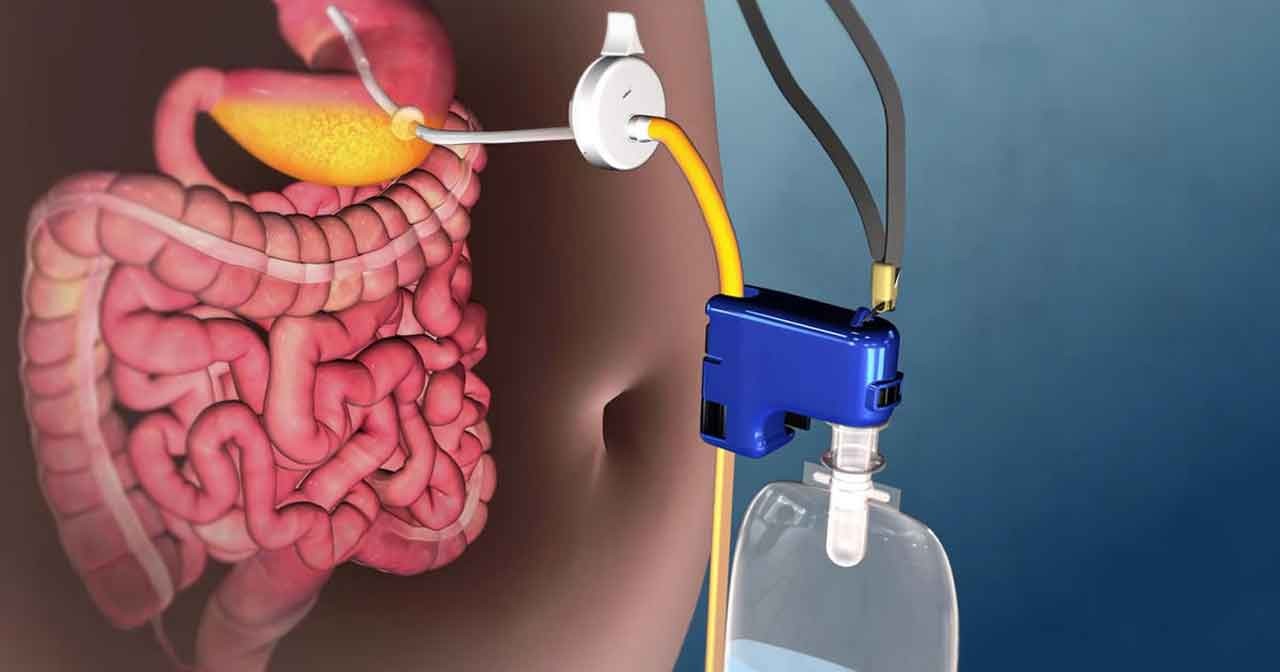

Now there’s another option, a device called the AspireAssist system, which the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for obese people who have not been able to lose weight through diets. A thin tube is implanted in the stomach that connects to an outside port on the skin of your belly. About 20 minutes after finishing a meal, you can connect the port to another device that drains about 30 percent of your meal into the toilet. You might use it two or three times a day.

The FDA made its decision based on research showing that people using the system lost 12 percent of their total body weight in the first year, compared to another group of similar people who tried to shed pounds without the device and lost only 3.6 percent of their weight.

You might consider AspireAssist if you have been debating whether to get a gastric banding procedure, considered the safest type of weight-loss surgery, although not the most effective. Most gastric banding patients lose 15 percent of their weight in the first year and remain stable over the next two. However, they often undergo another procedure, looking for more weight loss and help with diabetes and heart disease. AspireAssist is a less serious procedure than gastric banding.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Bariatric Surgery Can Reverse Type 2 Diabetes

A stomach-pumping tube sounds unpleasant but isn’t a new idea. Hospitals have used tubes to drain the stomach for many years, for example when a patient has been poisoned or overdosed on a drug. Doctors may pump you stomach, inserting the tube through your throat, to prepare you for a surgery. The AspireAssist device just makes it easier to do.

Shelby Sullivan, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and director of bariatric endoscopy at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has worked with patients using the system since 2009. She reports that users must eat slowly, chew their food well, and drink water with meals, and those changes account for at least a third of the weight loss. She has been a public advocate for the device, but declares that she has no financial interest in the AspireAssist device or the company that makes it.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: The Obesity Epidemic in America

The possible side-effects aren’t pleasant — they include nausea, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea. It’s also possible to have pain, bleeding, or an infection around the opening in your abdomen, and when the tube is removed, you could develop a fistula, an abnormal passageway between the stomach and abdominal wall.

A quarter of the volunteers testing it dropped out before the year-long study was up. But even after the study, about half of the volunteers continued to use their device.

Will pumping your own stomach be a long-term solution? That’s still unclear. Americans need to eat more vegetables and less junk food. Your gut bacteria may be a big factor in your weight, and a good balance of bacteria and better health will probably require a change in what you eat, not just how much. Along with food, the device will remove stomach acids and salts that people may need over the long run. Also, the body may adapt by making you hungrier. “How it will change the hormonal signals between the brain and the gut that regulate hunger is anyone’s guess,” says Daniel B. Jones, MD, director of the Weight Loss Surgery Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School.

Still, the bottom line is that the country is getting fatter, diets routinely fail, and obesity shouldn’t be tolerated untreated. In an 18-year study of nearly 20,000 severely obese Americans, about half of whom had a gastric bypass procedure, the surgically-treated group was dramatically less likely to die of cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. Most patients are significantly thinner three years after the surgery, although they may regain some of their early weight loss.

Updated:

December 07, 2016

Reviewed By:

Christopher Nystuen, MD, MBA